Don't Fence Me In - Big Bend National Park, Texas

Getting There: Midland, Odessa, and the Permian Basin

I was already working in Dallas that week, which made it convenient to route my trip through the Midland–Odessa region. Instead of connecting through El Paso or Albuquerque, I flew directly into Midland International Air & Space Port (Wikipedia, Airport site), the main gateway for West Texas and the Permian Basin.

There are multiple Southwest flights each day into Midland, which made the outbound leg simple. On the way home, it was just as easy to fly from Midland back to Columbus, Ohio.

I landed around 9 p.m., well after dark. Flying in, I was immediately struck by the sheer size of the city spread out below, and by the glowing light of gas flares scattered across the horizon. From the air, the region looked alive with industry — a constellation of orange flames burning steadily against the black desert.

On the return flight, which was during daylight, it became even more apparent just how much oil comes from this part of Texas. From above, the wellheads formed an unmistakable patchwork that stretched far into the distance in every direction. The scale of extraction is hard to grasp until you see it from the sky.

While in Odessa, I stayed at the Odessa Marriott Hotel & Conference Center, one of the nicer Marriott properties I’ve stayed at.

I shouldn’t have been surprised, but Odessa is deeply industrial in character. Evidence of oil drilling is everywhere — from service companies and massive industrial campuses to pumpjacks scattered across open land. The smell of petroleum products often hung thick in the air. Even at the airport, most of the advertisements were for advanced drilling systems, oilfield equipment, and specialized industrial services.

Traffic through Odessa was equally striking. The main highway runs straight through the center of town, and traffic moves fast — 75 miles per hour right through the city.

All in all, it was a fascinating place to transit in and out of. It offered a firsthand look at what it means to live and work in the center of West Texas, in the heart of the Permian Basin.

Big Bend National Park is roughly four hours south of Midland, so after landing I picked up a rental car from Enterprise Rent-A-Car and began the long drive into one of the most remote corners of the continental United States.

Big Bend: Don’t Fence Me In

Big Bend National Park has been on my list for a long time. Its reputation for remoteness, scale, and rugged mountain scenery makes it one of the most compelling running destinations in the lower 48. It is a place defined by distance — from major cities, from highways, from cell service, and from anything that resembles modern congestion.

The park was once known as “Texas’ Gift to the Nation,” a phrase that still feels appropriate when you see just how vast and intact this landscape remains. Big Bend sits at the far southern edge of Texas, wrapped around a wide curve of the Rio Grande, with Mexico stretching endlessly across the river. It is one of the largest, least visited, and most isolated national parks in the country.

The title of this trip — Don’t Fence Me In — comes from the classic song popularized in the 1940s. In those early days, the lyrics fit the region perfectly. West Texas was still defined by open-range ranching, where cattle roamed freely across enormous unfenced expanses of desert and grassland. That is no longer the case. Today, the drive into Big Bend passes through hundreds of miles of fencing, with barbed wire running in straight lines across the desert as far as the eye can see.

But for a runner, the song still fits.

Once you step onto the trails inside the park, the land feels limitless. The park stretches for more than 800,000 acres in every direction, and when you are running deep into the Chisos Mountains or across the desert flats, the sense of space is overwhelming. It is one of the most remote feelings I have ever experienced while running — the kind of place where the horizon feels impossibly far away, and the trail seems to disappear into the earth itself.

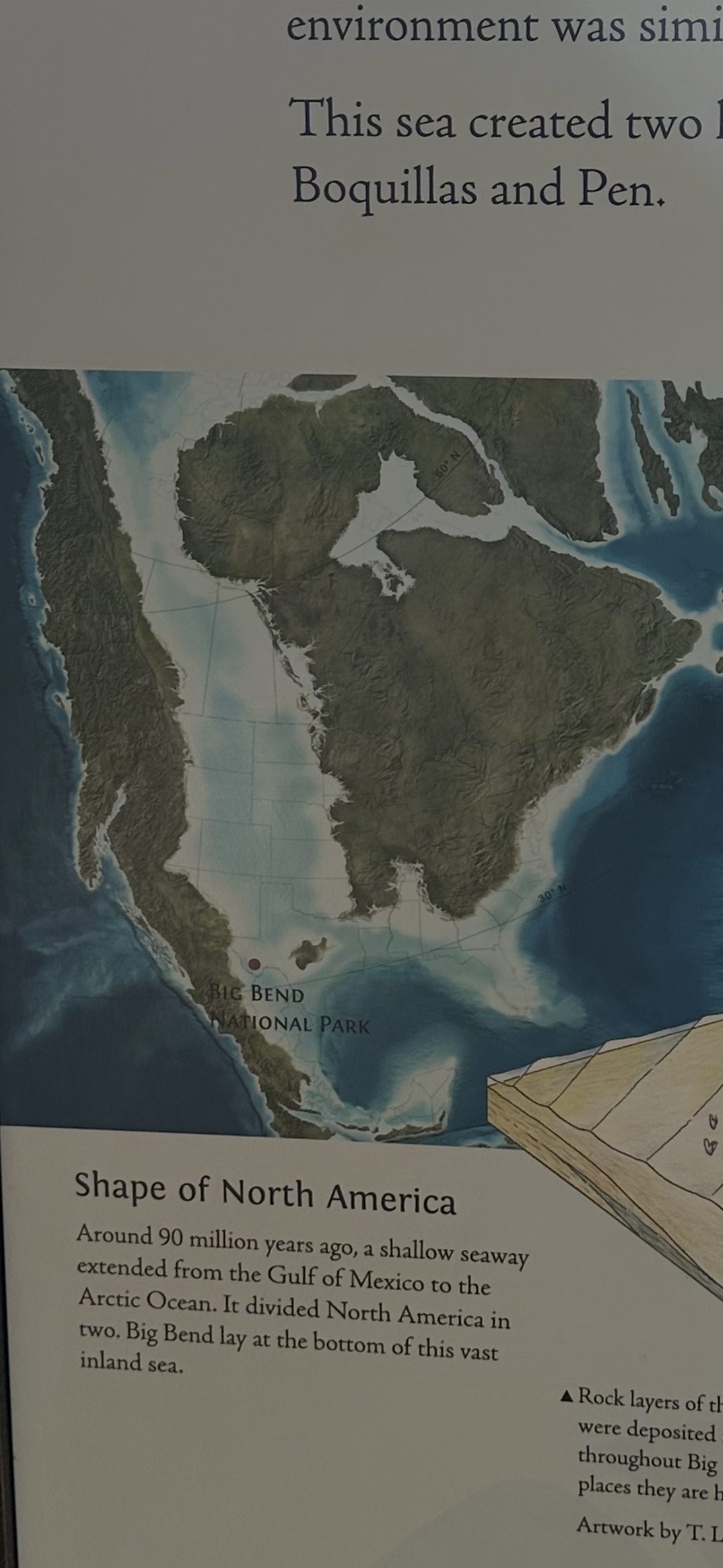

One of the most fascinating things I learned while visiting Big Bend is just how ancient this landscape is. Millions of years ago, an inland sea once cut across North America, covering much of what is now Texas. Big Bend was shaped by that sea, and when it finally receded, the region became a land where dinosaurs once roamed. Fossils are still found throughout the park, and there are multiple documented sites, including one right off the road that I stopped to visit.

The geology here is a reminder that this desert was once underwater, then jungle, then grassland, before becoming the rugged desert mountain range that exists today.

I am especially grateful to the Civilian Conservation Corps who, in the 1940s and 1950s, quite literally carved a road into the Chisos Mountains. Their work made it possible to reach what is now the heart of the park: Chisos Basin. Without that road, there would be no lodge, no campground, and no easy access to some of the best running terrain in the park.

I stayed at the Chisos Mountains Lodge, a small, quaint lodge tucked high in the basin and surrounded on all sides by dramatic volcanic peaks. It has just enough amenities to support a short weekend adventure — a restaurant, a small store, and simple rooms — but the real luxury is location. From the front door, I could step straight onto the trails and begin running into one of the most remote landscapes in North America.

In a state known for highways, fences, and private land, Big Bend still feels wild. And when you are moving through it on foot, mile after mile, the words don’t fence me in take on a very real meaning.

Running the Chisos: The Window Trail and Oak Spring

My first run in Big Bend started almost immediately after I arrived.

I reached Chisos Basin around 3 p.m., but check-in at the lodge wasn’t until 4 p.m. With plenty of daylight left — sunset wouldn’t come until around 6:30 p.m. — I decided not to wait. Instead, I changed in the parking lot, pulled on my running gear, and headed straight for the trail.

Dressing was a little tricky. It was in the mid-30s Fahrenheit (around 2–4°C), but the sun was strong and the sky completely clear. I knew once the sun dropped behind the mountains it would get cold fast, so I layered carefully and carried just enough to stay warm on the return.

The first run was on The Window Trail, one of the most popular hikes in the park and an ideal introduction to running in the Chisos.

From the basin, the trail drops roughly 1,000 feet (about 305 meters) over the course of the route, descending steadily through desert vegetation and volcanic rock. I was surprised to pass several groups of hikers heading down so late in the afternoon, especially given how quickly darkness would arrive.

The trail is very runnable for most of its length. There’s a mix of smooth singletrack and stone steps carved directly into the mountainside. Only near the very end does it become more technical, with looser rock and a need to slow down and watch your footing.

At the bottom, the trail opens up to The Window, a massive V-shaped pour-off that frames the desert floor far below. The view is extraordinary. Looking out through the opening, the desert stretches endlessly toward the Rio Grande, with layers of ridges fading into the horizon. It was well worth the run.

After a short pause at the viewpoint, I turned around and began climbing back up toward the basin. Not far into the return, I reached the junction with the Oak Spring Trail. On impulse, I decided to take it.

Oak Spring adds more elevation and traverses the side of the mountain on a narrow, beautifully cut trail. The route contours along steep slopes with long drop-offs to one side and sweeping views across the park. It was some of the most fun running of the trip because it is smooth, fast, and dramatic, with the entire expanse of Big Bend laid out below.

I ran about a mile (1.6 kilometers) out on Oak Spring before turning around. The light was starting to soften, and I didn’t want to risk being caught out after dark.

Back on The Window Trail, I began the long climb back to the basin — roughly 1,000 feet (305 meters) of gain. About a mile (1.6 kilometers) from the trailhead, I passed several large groups heading down, many of them lightly dressed and clearly unprepared for the temperature drop that was coming.

At the time, I was mostly focused on getting back before dark. Only later would I realize just how black Big Bend becomes at night — a level of darkness that swallows the mountains, trails, and desert completely.

I’ve often wondered what those groups ended up doing.

My Evening in the Basin

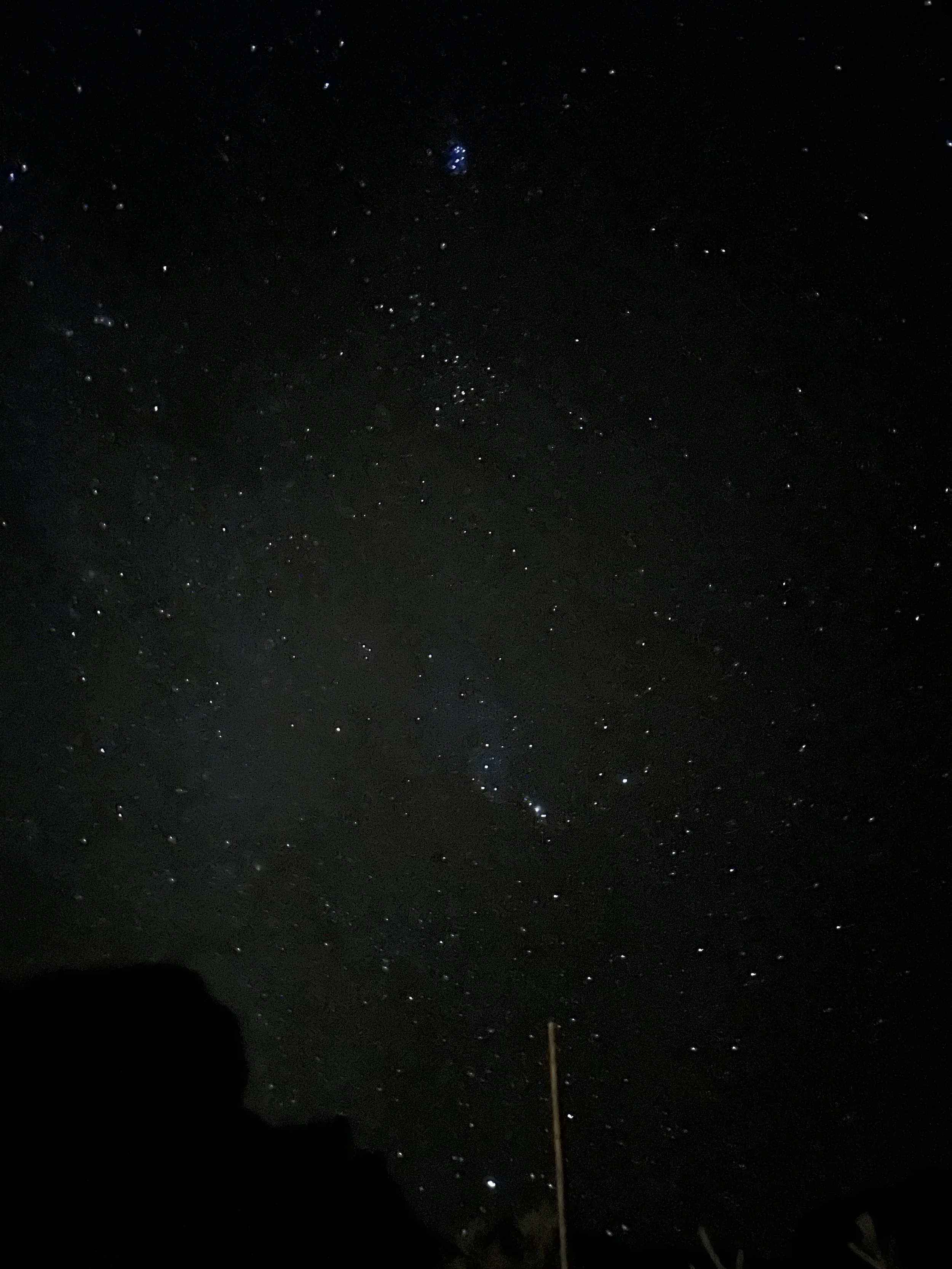

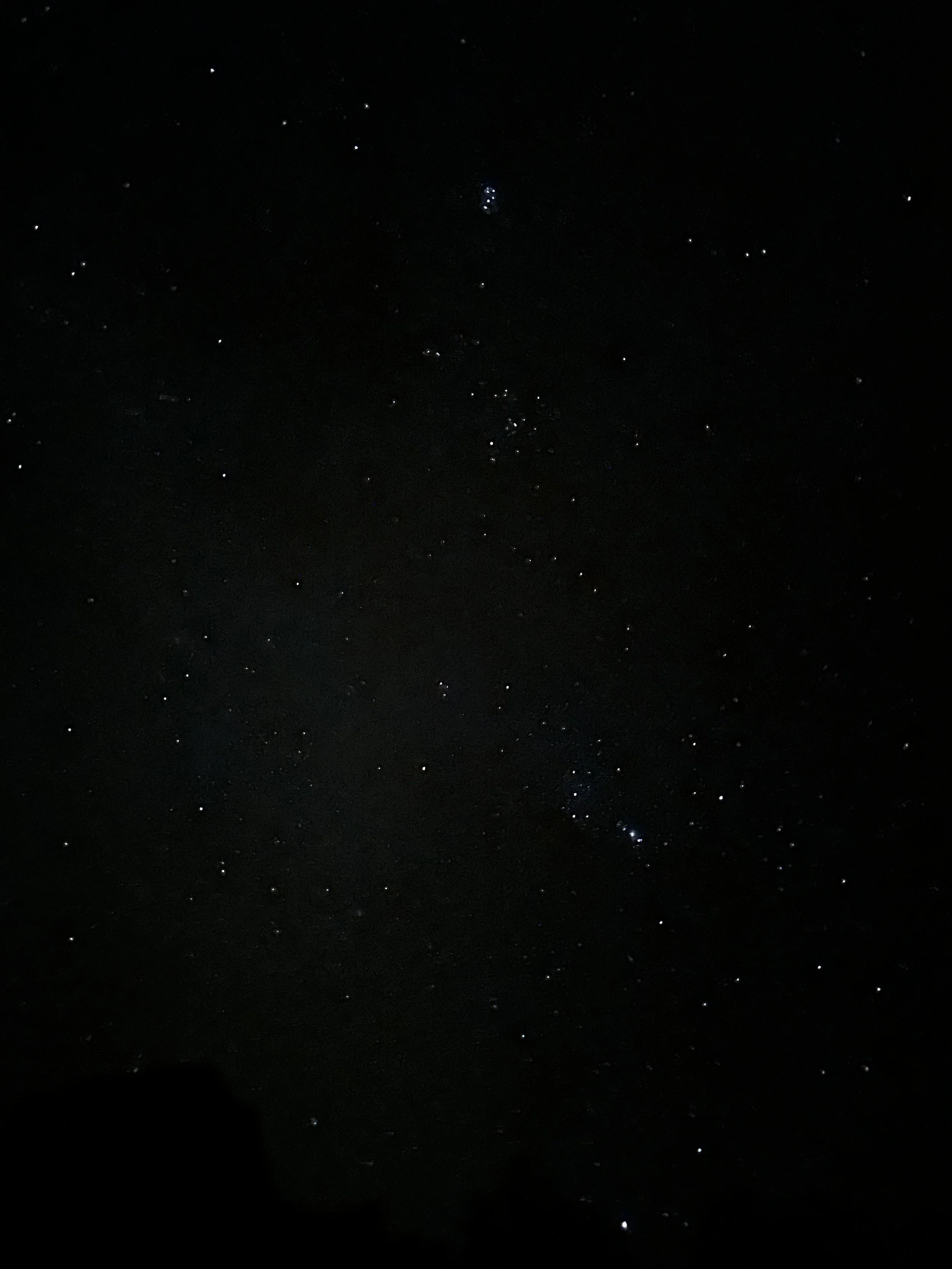

One of the most unexpected parts of the trip was just how dark it gets at night in Big Bend. With no nearby cities and almost no light pollution, the basin disappears completely once the sun drops behind the mountains. The sky turns deep black, and the stars feel closer and brighter than almost anywhere else I’ve been. I took a short evening hike around the basin, letting my eyes adjust to the darkness, and spent time just standing still and looking up.

It was also exceptionally quiet. There were no distant highways, no aircraft overhead, and no background hum of civilization. Just the sound of the wind moving through the trees and across the rock walls. I pulled out my iPhone and took a few long-exposure night photos, surprised by how much it was able to capture. I’m not even sure if I saw the Milky Way that night, but standing there in the silence, surrounded by darkness and stars, it certainly felt possible.

The Main Run: A Chisos Mountain Loop at Sunrise

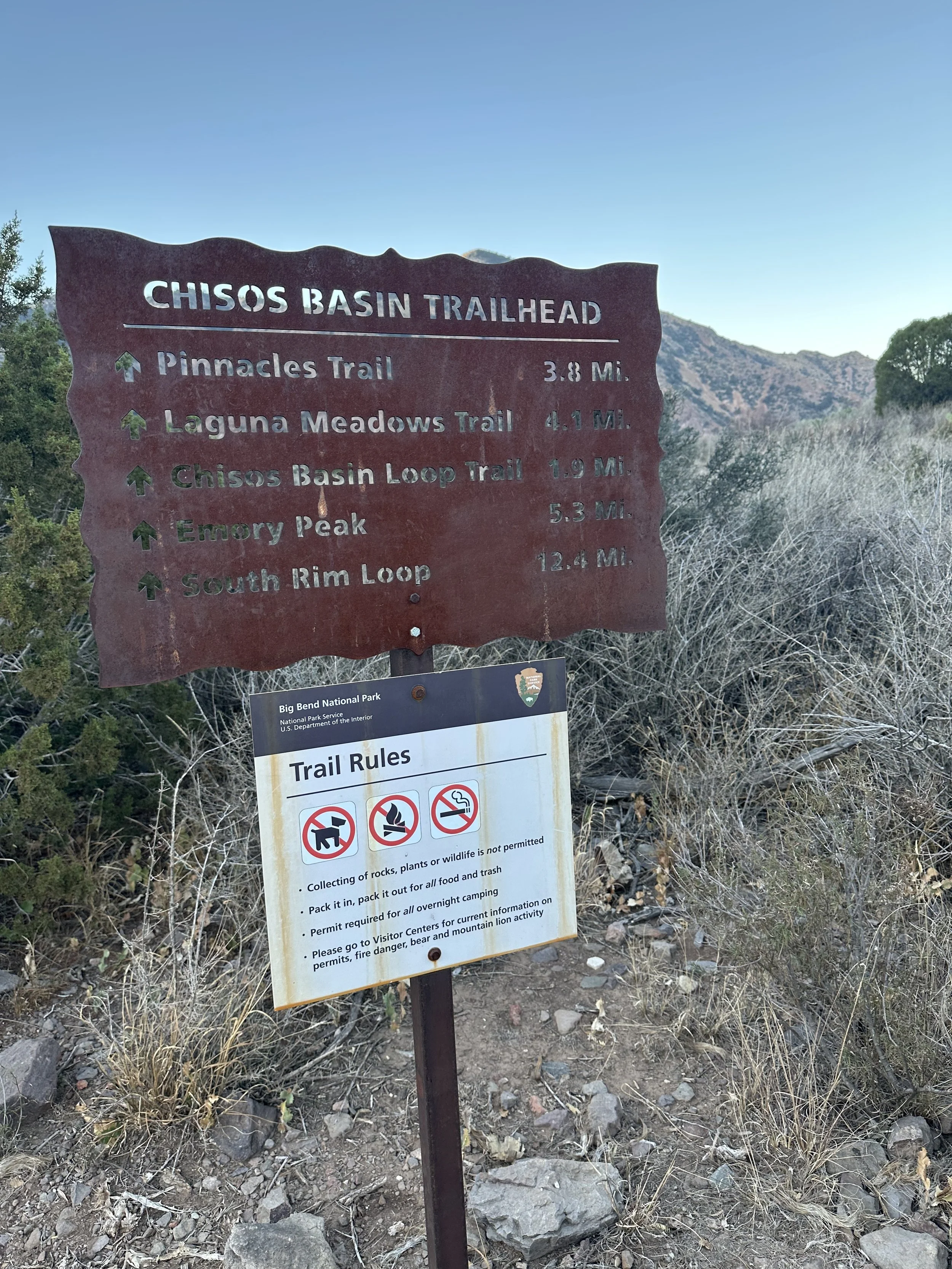

The main run of the trip was a 15-mile loop (24.1 kilometers) that starts and ends right at the Chisos Mountains Lodge, which sits at approximately 5,400 feet (1,646 meters) above sea level. One of the great advantages of staying in the basin is that you can step out your door and immediately be on world-class trail.

I decided to start right at sunup. That would give me plenty of daylight to finish the run, pack up, and still have enough time to drive back north to Midland while the light was good.

The morning was cold, with a steady breeze moving through the basin. Temperatures were in the 30s Fahrenheit (around 1–4°C), and the wind made it feel even colder in the shade. I packed conservatively: 3 liters of water, gummy bears and twix bars, two extra long-sleeve shirts, and full all-weather gear, pants and a jacket, in case the run took longer than expected.

Within the first mile (1.6 kilometers), I was already too warm. The climb started immediately, and I quickly worked up a sweat. I stopped briefly to take off my fleece and switched to a single long-sleeve shirt, which proved to be the right call for most of the run.

One of the biggest surprises of the morning was how much of the route stayed in shade or under tree cover. The Chisos are far greener than most people expect from a desert park. When I was out in the sun, it felt pleasant despite the cold air. In the shade, though, the temperature dropped sharply. I was glad I had my gloves and they stayed on for almost the entire run.

The first 5 miles (8 kilometers) are mostly a steady climb, gaining roughly 2,500 feet (760 meters) on the way toward Emory Peak, which rises to approximately 7,480 feet (2,280 meters). The trail is smooth and highly runnable, winding through pine, oak, and juniper forest. Only the final approach to the peak requires a short scramble, where hands are needed to navigate the volcanic rock.

From the summit, the view opens wide across the park. Layers of desert ridges stretch endlessly toward the horizon, with Mexico visible far to the south. I passed a few small groups and solo hikers on the way up, all moving quietly through the cold morning air.

It was quite windy at the top, so I didn’t linger long. I turned back down and continued on toward the South Rim, where the character of the run changes completely.

The trail weaves in and out of small valleys, staying mostly protected among trees and rock walls. Then, almost suddenly, the land drops away.

The South Rim is where you see the true scale of Big Bend.

From the edge, the park unfolds in every direction with rolling hills, deep valleys, dry riverbeds, and distant ridgelines fading into blue haze. The Rio Grande cuts a faint line far below, tracing the border between Texas and Mexico. It is one of the most dramatic viewpoints anywhere in the national park system.

I ran along the crest for a while, enjoying the exposure and the constant, shifting views. Eventually, the trail turned back toward the basin and the lodge. From there, it was a long, flowing descent with smooth singletrack, well-built switchbacks, and just enough technical sections to keep things interesting.

By the time I reached the basin, the temperature was already starting to drop again and the wind was picking up. I was glad I finished when I did.

It was one of my favorite runs I’ve done anywhere — a true mountain loop in the heart of one of the most remote landscapes in the United States.

Final Thoughts

Big Bend is a place that stays with you long after you leave. From running beneath the towering walls of the Chisos to standing on the South Rim with the desert stretching endlessly toward Mexico, it delivers a rare combination of scale, solitude, and true wilderness. It is the kind of landscape that makes distance feel small and effort feel meaningful. If you are drawn to remote trails, big mountain views, and places where the horizon seems unreachable, Big Bend belongs high on your list. And if you are looking for more places like it, you can explore dozens of other ultrarunning destinations from around the world throughout the rest of this site.

Tracks

Window Trail

Start and End: Chisos Mountain Lodge

Distance: 6.5 miles (10k)

Elevation Gain: 1,192 feet (363m)

Emory Peak and South Rim Trail

Start and End: Chisos Mountain Lodge

Distance: 16 miles (26k)

Elevation Gain: 3,576 feet (1,090m)